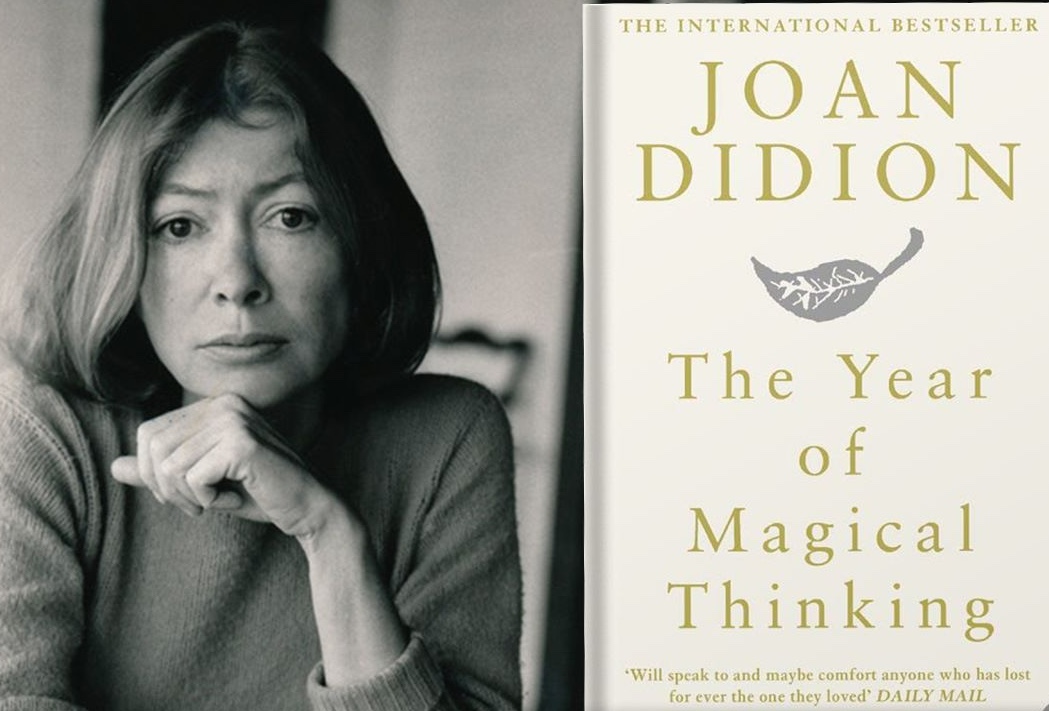

For me, few books confront grief with the unflinching clarity of Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking. It is one of my favourite of Didion books and I reread it recently.

Didion wrote it in the aftermath of her husband’s sudden death; it isn’t a memoir of healing so much as a dissection of loss, precise, restrained, devastating.

The book begins so memorably and so starkly. It grabs you and doesn't let go:

“Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner, and life as you know it ends.”

From that point forward, Didion offers no arc of redemption. There’s no resolution, only the work of attention.

At first glance, it’s a book about mourning. But on a second reading, it becomes clear that The Year of Magical Thinking is also a book about language—or rather, its failure. Faced with the collapse of her world, Didion turns to the only tool she has: sentences. Not memories or mantras, but syntax. Her grief unfolds through grammar.

What makes this book so compelling is its refusal to sentimentalise. Didion doesn’t aim to comfort, nor does she offer tidy insights. She writes as if by compulsion, returning again and again to the barest facts, as if precision might yield resurrection:

“He was dead. I was not yet prepared to accept this.”

Language fails her, and she knows it. Yet she continues, because the sentence is all she has. It becomes her vigil, her protest, her scaffolding.

There is something deeply recognisable in her portrayal of loss. It doesn’t follow stages. It wanders, fixates, and doubles back. She keeps her husband’s shoes because he might need them. She traces the mind’s quiet absurdities, the desperate logic of magical thinking. In doing so, she reveals how grief not only fractures the future but also unravels the present and past.

Still, The Year of Magical Thinking is not only about death. It’s about the stories we tell to survive. About love, memory, time, and the fragile architecture of meaning we build around ourselves. What elevates the book is Didion’s ability to move from the forensic to the metaphysical. A detail about medical records carries the weight of existential crisis. She shows us that writing can hold space for the unbearable.

Much of this impact stems from the way she writes, not just what she says, but how she does so. The Joan Didion sentence is unmistakable. Cool, controlled, and exacting, her prose does not shout. It slices. Her sentences are short, rhythmic, and often recursive. She uses repetition not for emphasis but for survival. She withholds obvious emotion and lets structure carry the weight.

Her voice is often called icy or clinical, but that misses the urgency beneath. Didion’s clarity is not dispassion; it’s strategy. Her language is exact because her world is not. If grief is chaos, then grammar, however fragile, is an act of resistance.

If you want to write like Didion, don’t try to imitate her tone. Instead, study how she builds control from collapse:

The Didion Sentence Toolkit:

1. Keep it short – especially the emotional hits.

2. Use repetition for rhythm, not filler.

3. Let the sentence end abruptly. Don’t explain.

4. Pair specificity with mystery, as she does in her novel Play it as it Lays – “I know what ‘nothing’ means, and keep on playing.”

5. Let syntax mimic feeling – clipped for shock, winding for reflection.

Didion doesn’t offer catharsis. She offers structure. For those who have grieved, this book is a mirror. For those who haven’t, it is a lesson in bearing witness. Either way, it lingers. Not because it resolves anything, but because it doesn’t.

It says: This happened. This is how it felt. And sometimes, that’s all a sentence needs to do.

No comments:

Post a Comment